Comedy Book: How Comedy Conquered Culture—and the Magic That Makes It Work

amazon.com

I am a long-time comedy enthusiast. How long? I bought and shared Tom Lehrer’s records. Lenny Bruce. Groucho. Cosby. Allan Sherman. Vaughan Meader. Smother’s Brothers.

https-cdnsimages.dzcdn.net_images_cover_2ee9664f86763b5c2fc9b02d96218c40_1900x1900-000000-80-0-0.jpg

Because of this life-long interest, I have been listening to Jesse David Fox’s Good One podcast for many years. Fox’s podcast is highly instructive and thoughtful and has enriched my comedy knowledge, with pleasure.

pod.link

While listening, I imagined a comedy unit for high school English. Comedy could become a great unit: it involves manipulating language, personal and social commentary, and imagination—three qualities that are important in an English course and would engage students. So I was very excited when I saw this book.

And it has not disappointed. Fox is both informed and thoughtful, giving me lots to think about and fuel my wish to have a comedy unit in an English course.

What excited me even more was that Fox’s approach to comedy and its uses aligned with my enthusiasm for media literacy education. For example, Fox thinks that comedy plays an essential role in our lives and that we need to pay more attention to it. Substitute media literacy for comedy and I’m happy to see their mutual benefits.

Even though the book never mentions media literacy, the AML Key Concepts just jump off the pages. Media experiences construct versions… Audiences negotiate… Media experiences have social and political… Media experiences have aesthetic… (This, of course, from a highly-biased reader who sees the Key Concepts everywhere. But still…)

Fox’s book posits an advanced and crucial role for comedy in our lives. Specifically, he suggests that society might use comedy to process some of its most challenging ideas. He is also suggesting that there is not comedy, but comedies. He suggests that—as a result of the digital environment—comedy has changed profoundly in its form, content and impact. This has been especially the case for stand-up comedians, some of whose reputations have gone from minor celebrities at best to seers, shamans, soothsayers, oracles, etc. Ironically, it is as though history’s medieval fool has discovered and conquered the internet. Dave Chappelle signed a $20-million-per-release comedy-special deal with Netflix and released six stand-up specials under the deal. (Wikipedia)

https-__news.newonnetflix.info_wp-content_uploads_2018_08_the-best-standup-aug-2018.jpg

Comedy Book uses the term joke jokes to label the kinds of jokes told by stand-up comedians during the prehistory of the digital age. These are jokes that comedians deliver in a stand-up set that are loosely-connected to one another. They may have a general topic or theme but are just intended to elicit laughter and not much more. Although he doesn’t cite Henny Youngman specifically, Youngman’s comedy exemplifies the term joke jokes:

“Take my wife, please!”

“A man goes to a psychiatrist. The doctor says, “You’re crazy.” The man says, “I want a second opinion!” “Okay, you’re ugly too!”” (www.brainyquote.com)

Fox suggests that comedy evolved significantly as a result of the digital environment. He cites the fact that the ‘tight eight minutes’ that was the traditional set length for comedy clubs became hour-long specials and that the intimate comedy club sets evolved into large theatre specials recorded with live audiences, then shared on streaming services. So the technical affordances of sharing longer comedy shows asynchronously by streaming services has boosted the reach and impact of comedy. Also, streaming networks can’t easily program eight-minute sets, so the hour-long set evolved to suit networks’ marketing and distribution needs, i.e., NOT comedy’s needs.

Expanding from a tight eight minutes to an hour has created opportunities and pressures. Specifically, comedians have woven their jokes into longer narratives. Instead of a string of loosely-connected jokes on two or three topics, the jokes become illustrative within a larger story arc or idea. Comedians can take an idea and explore, develop and twist it into an engaging and potentially meaningful saga. Jokes can be set up in the first ten minutes and then revisited in the conclusion. It’s as though an anecdote has morphed into a novel, or at least a short story.

The digital environment has also impacted audiences. Almost all comedy specials are recorded before live audiences, which are sitting in the theatre and react in real time. Camera and editing are used to show audience reaction, so the audiences become characters or props in the performance. But then there is the online audience, which might be consuming the comedy in very different circumstances: with or without other people; on a large or small screen; all at once or in installments; in its original language or in translation; fans or haters. I reference the haters audience portion because haters would be unlikely to attend a live show but might very likely view a recorded presentation. This also makes them part of the evolution of comedy facilitated by the digital environment.

And because it’s a digital delivery and experience, there is also social media in the mix, where people can critique, express their fandom or their displeasure. Just as the editing of the recorded face-to-face performance might include audience responses, the digital audience is represented by its social media responses.

Fox’s main point, which he illustrates comprehensively with both theory and example, is that comedy is fulfilling an important—if not essential—function in helping people process large, complex and challenging ideas. He presents many examples, but two really helped me understand his points.

One is The Daily Show (when John Stewart hosted). Stewart was both a guide and teacher in helping people—and The Daily Show staff—think critically about current events. He is credited with encouraging his audience to consume and reflect on news reports. In fact, many people got their news from The Daily Show and, because Stewart’s critiques were wrapped in comedy, audiences were encouraged to continue watching. Many standup comedians use humour to engage and explore challenging ideas as a result of Stewart’s influence. And stand-up has become more political and self-conscious.

Wikipedia

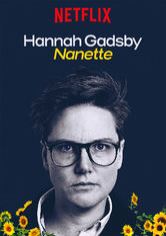

Another significant event cited in the evolution of stand-up—especially the long-form narrative—is Hannah Gadsby’s Nanette. Fox suggests that Nanette used stand-up codes and conventions to challenge—even destroy—traditional stand-up. Specifically, he explains how Gadsby provided many jokes in the first portion of their performance, then removed all the humour in the second portion to illustrate stand-up’s qualities and foibles.

Wikipedia

Nanette’s success freed comedians from having to tell a string of loosely-related jokes and allowed them to sometimes just tell stories (i.e., with less pressure to tell jokes), reflect and deal with really big ideas. It also helped audiences understand and appreciate their relationship to stand-up and comedians. Gadsby directly referenced the codes and conventions they were using in Nanette, helping audiences become more aware of stand-up techniques and of their own responses.

There are many other ideas and comedians cited in Comedy Book. It’s compelling and a great example of critical thinking and synthesis. It’s also a great example of media literacy thinking.

There is a great English class comedy/media unit waiting to be developed.