IMLRS 2024 – Azores, Portugal: A Perspective by Carol Arcus

Attendees of IMLRS2024 found themselves in a delightful semi-tropical setting, with a perfect temperature range of 19-23C. It was an intense 2 days, with talk ranging from the inevitable “AI in the classroom” to a robust deconstruction of media reportage in the first few days of the Israel-Hamas war (Evanna Ratner).

I begin here with a collage of images representing the IMLRS experience, July 27-28 2024. Ponta Delgada, San Miguel, Azores, Portugal. This is followed by summaries and critical inquiry into the presentations I attended.

*

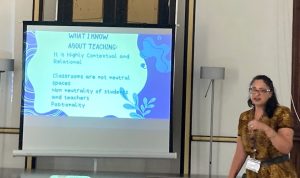

The Meme Conundrum: Y U No Understand? – Diana Maliszewski

Teacher-librarian and media literacy educator in the Toronto District School Board. She represents Canada on UNESCO’s Media and Information Literacy Alliance for North America and Europe and is the vice-president of the Association for Media Literacy. She also teaches school librarianship courses to K-12 educators for York University and Queen’s University.

Children today watch YouTube and TikTok, influencing their pop culture references and humor. This “chair talk” demonstrates the value of understanding memes as media references to help students grasp complex messages and engage in different subject areas. Teachers can then incorporate these ideas into their practice.

https://www.kidizen.com/items/family-meme-night-game-15162026

This session was easily one of the most stimulating and immediately accessible of all those I attended. Diana demonstrated a class activity in which students were tasked with sorting appropriate from inappropriate memes, using contextualization to explain their reasoning through the “Identify – use – explain” method. They were encouraged to discuss why some memes were not understood and what they might mean, and to create a meme to express their current feelings. Wall conversations with post-its allowed further discussion about memes.

The discussion highlighted the fact that while some students view “bad” memes as “good because they’re bad,” they should be encouraged to explore the deeper meanings. Simple answers like “I don’t know” should be challenged with prompts to understand the history behind the memes they enjoy. Students should be asked to track meme references, acknowledging that “references have references,” which underscores the intertextual nature of memes. For example, someone dressing like a character from the film Carrie and wearing a shirt with the high school’s name illustrates cultural exchange.

Memes have cultural and specific meanings, acting as cultural codes that organize us socially. They are performative and help students understand media better. Teachers should engage students in conversations across different cultures to compare meanings and move them beyond surface-level understandings.

Useful resources include the website Know Your Meme for meme history, and the game Family Meme Night (see above), which demonstrates there are no right answers in understanding memes. Additionally, Claire Wardle’s work on misinformation provides further insights into memes. This Chair session also considered the existence of memes as cultural pieces before the Internet, and discussed how LGBTQ memes retell community history with insider language and identity codes – an example being ‘Stonewall’, the 1969 riot in NYC.

Critical questions arising from this presentation:

– What criteria might students use to distinguish appropriate from inappropriate memes?

– How can teachers encourage students to explore the deeper meanings behind the memes they enjoy?

– What might be the advantage of understanding the history behind a meme?

– How might memes serve as cultural codes that organize us socially?

– What strategies can teachers employ to facilitate conversations across different cultures to compare meme meanings?

– How did memes exist before the Internet, and how were they culturally significant?

– How can memes serve as tools for preserving and teaching about community history and identity?

*

Media Literacy + Information Literacy: Converging Spaces/Transcending Silos

Spencer Brayton, Natasha Casey, David Buckingham, Karen Ambrosh, Alaa Al-Musalli, Ki Wight, and Marcus Leaning

Panelists discuss the special winter 2023 issue of the Journal of Media Literacy, featuring David Buckingham’s critique of information literacy and responses from Andrea Baer, Andrea Gambino, and Renee Hobbs, debating whether media and information literacies are akin to different flavors of ice cream with shared ingredients or if their definitions have significant political and pedagogical implications.

4 key takeaways:

- The far right opposes media literacy, viewing it as a technique with normative assumptions.

- Importance of training into maturity (Al-Musalli), understanding the difference between intentionality and unintentionality, and effectively evaluating understanding, along with recognizing all influences and avoiding simplistic moral stances.

- Media literacy faces an epistemological problem, with the far right intolerant of doubt and complexity, preferring uncomplicated faith, making the challenge of addressing these issues more difficult.

- Concept of “literacy” was critiqued for its limitations, with mentions of living ‘in’ and ‘through’ media (M. Hoechsmann) and “literacy” being seen as mere rhetoric (D. Buckingham).

Critical questions arising from this panel:

– How might educators address the concerns raised by the far right regarding media literacy?

– What might be the key distinctions between intentionality and unintentionality in media literacy training? How might educators effectively train students to understand these differences?

– How might educators avoid promoting simplistic moral stances in media literacy?

– Why might some critics, like David Buckingham, view “literacy” as bland and rhetorical?

– What might be some common epistemological problems faced by media literacy education?

– Why might some prefer uncomplicated faith over the complexity inherent in media literacy?

*

C. Arcus & Alice Lee

From Gen Z to Gen Z: Teaching and Promoting MIL through Service Learning

Alice Lee – Hong Kong Baptist University (HONG KONG)

This paper introduces service learning as a new pedagogic approach to teaching and promoting MIL in the community, highlighting the involvement of 118 university students from Hong Kong Baptist University who taught MIL to Gen Z school children and young adults. It discusses the achievements, challenges, and benefits for both the service targets and the university students, emphasizing the student-centered nature of the approach, the combination of online and offline interactions, and its implementation in non-school settings.

3 key takeaways:

- A student-centered approach in MIL education enhances university students’ learning by engaging them and making the content relevant, helping them develop critical thinking, media analysis, and communication skills.

- Integrating both online and offline methods in service-learning projects presents challenges, such as technical difficulties and coordination needs, but offers increased engagement and improved learning outcomes for school children and young adults in non-school settings.

- These MIL projects help school children and young adults develop skills to critically evaluate information and use media responsibly, with potential for scalability and adaptation to other communities, extending their benefits and impact.

Critical questions arising from this presentation:

– How might a student-centered approach be tailored to meet the diverse interests and needs of all university students involved in the project?

– What specific MIL teaching methods or activities might prove most effective in developing critical thinking, media analysis, and communication skills?

– In what ways might conducting MIL education in non-school settings specifically enhance engagement and learning outcomes compared to traditional school environments?

– How might the impact of MIL education on school children and young adults be measured to ensure they are effectively gaining critical evaluation and responsible media usage skills?

– What role might community partnership play in the success of such MIL education projects, and how can these partnerships be fostered and sustained?

*

Developing Visual and Conspiracy Prebunking: A Dual Approach for Enhanced Media Literacy in Postmediality

Nicola Bruno and Stefano Moriggi: University of Modena and Reggio Emilia (ITALY)

This research presents an innovative media literacy approach that emphasizes preventive ‘prebunking’ strategies against misinformation, integrating visual and conspiracy prebunking to develop critical awareness and resilience, and demonstrating its effectiveness in teacher training courses for a post-truth era.

3 key takeaways:

- The presentation emphasized cognitive resistance as an effective methodological strategy, framing the environment as a social organization responding to specific adaptive challenges, including forewarning, preemptive measures, micro-dosing with weak examples, and activation through a toolkit.

- Strategy includes an interactive workshop that addresses conspiracy thinking, manipulation techniques, and creating multimedia outlets, where participants microdose on existing and fake conspiracies to develop awareness, culminating in the creation of their own conspiracy theories.

- Teacher training focuses on improving the ability to identify de-contextualized photos and encourages developing a conscious “eco-system” that goes beyond distinguishing true from false.

Critical questions arising from this presentation:

What might be the advantage of framing the media environment as a form of social organization help in addressing adaptive challenges?

What might be the benefits and potential drawbacks of forewarning and pre-emptive measures in combating misinformation?

How might explanations vs micro-dosing help participants develop a consciousness?

How might developing a conscious “eco-system” extend beyond distinguishing true from false information?

*

Quo vadis, media literacy?: Notes from the USA, Bulgaria, and Latvia

Barbara Ruth Burke and Liene Ločmele: University of Minnesota (USA) and Vidzeme University of Applied Sciences (LATVIA)

Investigating and comparing the state of Media and Information Literacy (MIL) education in the US, Latvia, and Bulgaria through policy documents, media texts, and interviews, Burke & Locmele found that while the status of MIL education differs among these countries, it is similarly influenced by political factors in all.

3 key takeaways:

- In Latvia, the focus is on combating misinformation by emphasizing a single truth, targeting seniors through direct messaging, promoting media and information literacy (MIL) among youth, and ensuring children’s safety to build societal resilience.

- In the US, efforts target seniors and children, addressing health and wellness, representation in education, and recognizing news bias and propaganda using the SIFT system to train individuals to contextualize information within ideological frameworks.

- Bulgaria emphasizes media independence and bias, combating misinformation and propaganda, and protecting both youth and seniors, with a final focus on civil engagement, advocating for a shift from mere approval of MIL initiatives to fostering creative thinking and shared responsibilities in creating and sharing positive stories.

Critical questions that arise from this presentation:

How might political influences be mitigated to improve MIL education? Would this be an appropriate approach?

Does the promotion of MIL among youth and ensuring children’s safety actually contribute to building societal resilience, and what might that look like?

What might be the strengths and limitations of the SIFT system in training individuals to contextualize information and discern ideological biases?

What future strategies might be implemented to enhance MIL education globally?

*

Education by Design – Keynote Panel : “Where are we with Media Literacy Education? Where are we going?

Antonio Lopez; David Buckingham; Sally Reynolds

Sally Reynolds: Chief Operational Officer of the Media & Learning Association. Director of Media Literacy for EDMOeu as well observer in the European Commission’s Media Literacy Experts group.

Antonio Lopez: co-editor of The Routledge Handbook of Ecomedia Studies; Professor of Communication and Media Studies at John Cabot University in Rome, Italy.

David Buckingham: Emeritus Professor of Media and Communications at Loughborough University, and a Visiting Professor at King’s College, London University, UK.

Since 2016, media literacy education has evolved from addressing misinformation and disinformation to encompassing technology and justice issues; this panel discussed positives, concerns, and future focus suggestions.

3 key takeaways:

- Lopez emphasized the importance of kinship, responsibility, and ethical communication, advocating for empathy and treating environmental communication as a crisis discipline to address issues like climate disinformation and the spiral of climate silence, while criticizing corporations for shifting blame to individuals and suggesting peer teaching among students.

- Buckingham referenced Harvey Graff’s work, cautioning against viewing media literacy as a panacea, urging careful consideration of its effectiveness and definition, emphasizing that teaching about media is a duty for schools, and noting the decline of ”media education”, which should replace the term ”media literacy”.

- Reynolds raised concerns about measuring media literacy, maintaining its relevance amidst disengagement, and promoting civil discussion, suggesting Finland as a model for effectiveness.

Critical questions that arise from this discussion:

How might educators effectively integrate the concepts of kinship, responsibility, and ethical communication into media literacy curricula?

How might peer teaching among students enhance their understanding and practice of media literacy?

What might be the potential risks of viewing media literacy as a panacea, and how can these be mitigated?

How might the term “media education” better serve the goals of media literacy compared to the term “media literacy”?

Has media literacy become a Neo-Con argument, and what might be the implications of this shift for policy-making?

What lessons might be learned from Finland’s approach to media literacy, and how can they be applied in other contexts?

*

Techne Pedagogy: New Ways of Thinking about Knowledge in Creative Media Production

Steve Connolly – Anglia Ruskin University (United Kingdom)

Steve Connolly investigates the specific knowledge and skills needed in creative media production, focusing on what young people demonstrate when creating media texts and the pedagogical knowledge required by educators. Interviews with experienced media educators suggest that guiding creative production necessitates moving beyond traditional knowledge models like Pedagogical Content Knowledge and Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge. The nature of knowledge in creative production is intricate and demands new theoretical frameworks.

3 key takeaways:

- The presentation highlighted the importance of understanding students’ needs and the potential gap between what students need to know and what they do, raising questions about the role and knowledge of those who study student learning.

- Emphasizing the intersection of content and pedagogy, noting that critical thinking develops from questioning production work, with theorizing and production work having lifelong applications.

- The power of group work and the collaborative process in producing new knowledge, along with the importance of the recursive process of checking draft versions to reinforce learning and improvement.

Critical questions arising from this presentation:

How can educators determine what students need to know and then do, and how can they identify if these needs are the same?

How can the intersection of content and pedagogy be effectively navigated to enhance student learning?

In what ways can criticality be fostered through questioning production work, and how can this skill be measured?

How can production work be integrated into the curriculum?

What makes group work powerful, and how can its benefits be maximized in an educational setting?

How does the recursive process of checking draft versions contribute to learning and improvement? What strategies can be employed to ensure that this recursive process is effective and meaningful for students?

*

Beyond Solutionism: Motivating Media Literacy with a Theory of Change

Julian McDougall is Professor in Media and Education and Programme Leader for the Professional Doctorate (Ed D) in Creative and Media Education at Bournemouth University, UK. He is co-editor of the Journal of Media Literacy Education and Routledge Research in Media Literacy and Education.

McDougall’s research indicates that media literacy, influenced by sociocultural diversity and technological changes, requires redefinition and diversification, proposing a dynamic media literacy to foster positive social change and enhance media ecosystems in diverse societies.

2 key takeaways:

- McDougall emphasized the critical role of media literacy in the literacy ecosystem, highlighting the importance of intentional changes to address the complex nature of media environments and their active use.

- By applying a theory of change that understands and addresses these complexities, we can aim for a healthier future in media literacy.

Critical questions arising from McDougall’s presentation:

– How does media literacy fit within the broader literacy ecosystem, and what are its unique contributions?

– What roles do different stakeholders (educators, policymakers, media producers) play in integrating media literacy into the literacy ecosystem?

*

Ecomedia Literacy: A Strategy for Addressing Global Environmental Challenges

Antonio Lopez – a co-editor of The Routledge Handbook of Ecomedia Studies. He is Professor of Communication and Media Studies at John Cabot University in Rome, Italy.

Urgent media education action is crucial for addressing global environmental challenges and the climate emergency, with ecomedia literacy examining the environmental impacts of media and ICT. This systems-thinking approach provides an analytical framework for integrating sustainability into curricula, promoting the SDGs, and seamlessly incorporating sustainability into both scientific and liberal arts education.

2 key takeaways:

- Integration of media and environmental awareness through the 5 Es: Enclosure, Extraction, Expendability, Exploitation, and Externalization, highlighting how these concepts are crucial for understanding environmental issues.

- Media play a significant role in shaping perceptions of climate change, life under water, data interpretation, degrees of critical thinking about consumption patterns, and the diverse realities of the global south.

Lopez’s presentation raises the following critical questions:

– How might the 5 Es (Enclosure, Extraction, Expendability, Exploitation, and Externalization) interrelate to shape media and environmental awareness? What specific examples might illustrate the impact of each of the 5 Es on environmental issues?

– How might media coverage affect the public’s interpretation of environmental data & consumption patterns?

– How are the diverse realities of the global south represented in media, and what impact might this have on global environmental awareness?

– What might be the challenges and opportunities in using media to accurately depict environmental issues in the global south?

*

The Right to the Analogue and Media Literacy: Ethical and Legal Considerations

Georgios Terzis is a professor in Communications and Ethics at the Brussels School of Governance, Vrije Universiteit Brussel. Dariusz Kloza is a senior researcher at the Human Rights Centre at Universiteit Gent. He is also a senior data protection expert at the Brussels office of Van Bael & Bellis.

Georgios Terzis and Dariusz Kloza from Vrije Universiteit Brussel and Universiteit Gent explore the right to the analogue, emphasizing the choice to disconnect from the internet and new technologies, and the relation of this decision to media literacy. They argue that fundamental rights like privacy, freedom of expression, and non-discrimination can protect against mandatory inclusion, proposing a new right to support analogue life, with media literacy being essential in safeguarding this right through ethical and legal means.

2 key takeaways:

- Policy should be more democratic, defending individual interests and promoting the fundamental right to opt out of online life, emphasizing the protection and promotion of personal choice.

- Audience questions highlighted concerns about the feasibility of opting out in a deeply interconnected society, privacy and data issues, and the historical challenges of avoiding the pervasive effects of media, whether in the digital age or during the era of print.

Critical questions related to this topic:

– What role might media literacy play in supporting individuals’ choices to engage or disengage with digital technologies?

– How might the right to opt out balance with the societal expectation of digital inclusion and participation?

– What are the implications of recognizing a fundamental right to opt out of online life?

– How might such a right ever be effectively protected and promoted in policy and practice?

– In a deeply interconnected society, what are the practical challenges individuals face when attempting to opt out of online life?

– How might policies address issues of privacy and data protection for those who choose to opt out?

*

Generative AI and Media Literacy: The Perfect Storm

Silvia Frota: University of Lisbon/FLUL /CEComp (PORTUGAL)

The current communication technology stage brings radical transformation to media, with digitalization, increased connectivity, and accelerated data flows leading to media pervasiveness in all social spaces. News production now intertwines with information circulation, and the mediatization debate highlights changes in social institutions due to communication technology, including mass self-communication. The presentation analyzes AI media coverage by Portuguese newspapers.

2 key takeaways:

- The presentation explored media representations of technology, particularly AI, focusing on its potential, capacity, risks, normalization, and regulation, noting that AI’s potential receives more media coverage than its challenges.

- The relationship between media literacy and AI was emphasized, highlighting that media literacy is crucial for addressing trust issues, and underscoring the importance of discussing AI on a larger stage.

Critical questions arising from this research:

– How & why might the media representation of AI’s potential differ from its representation of AI’s risks and regulatory aspects?

– What might be the implications of the media focusing more on the potential & thus normalization of AI than on its risks and regulation?

– In what ways can media literacy help the public better understand and evaluate the trustworthiness of information about AI?

– What role should the media play in informing the public about AI regulations and the ethical considerations surrounding its use?

*

Media Literacy in Time of War using AI

Evanna Ratner – Head of film and media studies, The Arts Department at the Ministry of Education in Israel. Department of Media Studies and Media Literacy at the Gordon College of Education, in Haifa. Involved in teaching and research in teacher preparation and media literacy, Expert in “Dialogue through Media”, Peace Education and Technology and Innovation studies.

During the 7/10 Israel-Gaza war, social media discourse significantly shaped public opinion, with disinformation and misleading stories circulating widely, contributing to confusion and outrage. This created a battlefield of propaganda and fake news, challenging media educators in Israel to address disinformation, propaganda, and AI’s influence on social media narratives. Media educators faced immense pressure from various stakeholders when providing critical analyses of war reporting and highlighting propaganda techniques.

3 key takeaways:

- The presentation highlighted the collected footage from the war, including from the music festival, showing how Israeli media aimed to provide information and foster unity, illustrating the interplay between journalistic practices, government policies, and public sentiment.

- The influence of platforms like Telegram, which had Palestinian content watched by Israelis, and TikTok, which exacerbated dissent, emphasizing that all media, including coverage of the Ukraine war and US elections, is used to stir emotions.

- The role of Israeli journalists appeared as loyal to the people rather than the government, highlighting the audience’s role in negotiating meaning; impact of media literacy in the classroom was addressed with a focus on acknowledging biases.

Critical questions arising from this research:

-How might war as a “media event” influence public perception and understanding of the conflict?

-What ethical considerations might arise when using footage from events like music festivals in war coverage?

-How might journalistic practices and government policies interact to shape public sentiment during times of conflict?

-In what ways might the media balance the need to provide information and foster unity without compromising journalistic integrity?

-What might be the implications of platforms like Telegram and TikTok in disseminating content and exacerbating dissent during conflicts?

-What strategies might be employed to help audiences critically evaluate emotionally charged media content?

*

Beyond the Code: Exploring Emancipatory Approaches to Critical Algorithmic Literacy in Brazilian Schools

Mariana Ochs – University of São Paulo (BRAZIL)

This presentation explores approaches to develop critical algorithmic literacy in Brazilian K-12 education, integrating democratic values, equity, and social justice in a data-driven society. Collaborating with teachers, the project creates a hands-on, creative, and emancipatory approach and cross-disciplinary framework for students to critically assess and interact with algorithms, aligning with media literacy pedagogy as suggested by UNESCO and Brazil’s National Media Literacy Strategy.

2 key takeaways:

- The discussion highlighted the difference between fake and synthetic content, questioning what needs to be taught in today’s digital environment and addressing the invisibilization of the digital landscape and its future implications.

- To be algorithmically literate, it is essential to understand the presence of systems, possess relevant knowledge, and develop a critical appreciation of these technologies.

Critical Qs arising from this presentation:

– How might educators effectively teach students to discern between fake and synthetic content?

– What core competencies and knowledge should be included in curricula to address the complexities of today’s digital environment?

– What might be the consequences of the increasing invisibility of digital systems on users’ understanding and engagement?

– How might the “invisibilization” of digital systems impact transparency, accountability, and trust in technology?

*

Teaching Curiosity in the Classroom: A Practice Based Approach

Patrick Usmar – Auckland University of Technology (NEW ZEALAND)

Curiosity is essential for media practitioners, students, and educators, driving the exploration and application of media literacy skills. Young learners often struggle with nurturing interest curiosity, experiencing deprivation curiosity in a digital era filled with instant answers and misinformation. This action research-based project presents class exercises developed to improve higher education students’ ability to apply media literacy skills, asserting that abstract teaching methods can also stimulate abstract thinking and enhance curiosity in media literacy education.

2 key takeaways:

- The presentation included an assumption about the negative impact of screens and devices plus the decline in longform reading, on children’s curiosity and suggested changing their thinking to encourage intellectual exploration.

- Strategies such as banning phones and engaging in creative activities like photographing ”boring objects in interesting ways”, were discussed to foster curiosity and interest in children.

Critical questions that arise from this topic:

– What specific methods might be employed to effectively change the way children think, in order to foster curiosity?

– How might educators use technology in the classroom to promote curiosity and intellectual exploration?

– Do screens and devices specifically impact children’s ability to develop and sustain curiosity? How might we learn this?

– How might the curriculum be restructured to better support the development of curiosity in students?

– How might we know that the decline in longform reading affects students’ ability to think critically and explore topics in depth?

*

The Lost Goal of Media Literacy Education: Reconnecting to the Fields’ Humanistic Values

Yonty Friesem: Executive Director of Media Education Lab and an Associate Professor of Communication at Columbia College Chicago.

The phrase “media literacy” is widely used, but definitions vary among educators, students, librarians, scholars, administrators, practitioners, and legislators, leading to fragmented practices, advocacy, and legislation, with no consensus on its goals. This presentation will introduce historical definitions that have shaped current laws and scholarship, and propose a humanistic framework to clarify media education’s path toward freedom, depolarization, and well-being.

3 key takeaways:

- Media literacy is not merely a destination but a journey shaped by the individuals and communities encountered along the way, emphasizing community engagement over civic engagement.

- The journey encompasses self-actualization, esteem, belonging, safety, and physiological health, suggesting that understanding how media works is not enough to be truly media literate.

- It is not possible to be a racist and also truly media literate. The ultimate goal is to foster long-term societal change through this comprehensive approach.

Critical questions arising from the presentation:

– How might conceptualizing media literacy as a journey rather than a destination change the approach to teaching and learning it?

– Might media literacy contribute to self-actualization, esteem, belonging, safety, and physiological health? How might we learn about this?

– Why might understanding how media works alone be insufficient for “true” media literacy?

– How does the assertion that one cannot be racist and truly media literate align with the goals of media literacy education? From whose point of view? What might be the implications of this statement for media literacy curricula and pedagogy?