Are We Addicted?

Many families are concerned that they are spending too much time on their devices and/or spending time on the wrong activities. Many experts are happy to tell them that they are, but a more honest answer is, “We don’t know.”

How can we really know about the best quality and quantity of device time when we have never had this level of access and variety of electric activities before?

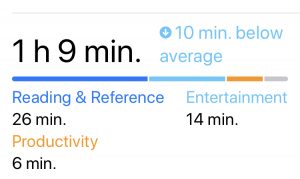

Metrics

What metrics can we/should we apply to measuring potential health risks of device addiction?

Are children addicted to devices, or to game-play, stimulation and variety? Haven’t they always pursued game-play, stimulation and variety?

Are teens addicted to devices, or to social connections and approval? Haven’t they always pursued social connections and approval?

A useful metric for device addiction is similar to that used for other addictions (drugs, alcohol, gambling): if the activities are negatively impacting other aspects of their lives or family obligations, then there is cause for concern. Specifically, if they are preferring their devices over eating, sleeping, or completing essential activities such as hygiene, homework or family duties, parents need to intervene.

Self-esteem

Children and teens with high self-esteem and proficiencies are often less vulnerable to device addiction. This is because they are getting their self-esteem and attention from other places than their app uses. Parents who provide opportunities for children and teens to develop self-esteem off-device (team activities, performing arts and clubs) can help them avoid or reduce their addictions.

Could time on the devices just be an excuse?

Are children and teens running into media environments, or away from home environments? I had a family member who was an avid—even obsessive—reader growing up. She didn’t really want to converse or share with her siblings, so she ‘buried her nose in a book’—an effective way to be physically present but mentally remote from her family. Are some children and teens avid device users in order to avoid family activities? If so, the problem may not be only with the devices.

Random Rewards and Addiction

Games and social media use random rewards—the strongest mechanism—to hold attention. Random rewards is the secret of gambling’s attraction. If someone wins consistently or at regular intervals, the predictability causes them to lose interest. But if they win unpredictably, randomly, they are compelled.

rnz.co.nz

When gaming on a device, meeting an unanticipated foe or condition provides the same random effect. Knowing that success and failure are just around each corner is compelling.

In social media, getting ‘likes’ or re-posts, which are dependent on others’ whims and availability, provides the same random rewards.

pngfind.com

Balance

How might families balance their online and offline activities? Families need to decide whether or not they have addiction problems, then decide what they might do about them.

First, they can articulate the addiction tests: preferring devices over eating, sleeping, or unable to complete essential activities such as hygiene, homework or family duties.

Once the problem is defined, they can decide what to do about it. Whatever the decision, it needs to be made collectively with children and teen participation.

Don’t phrase the solution in terms of the device, e.g., “I will spend less time on my device.” Rather, phrase it in terms of off-device goals, e.g., “I will complete my chores, homework, practice time.” “I will achieve at least a B average at school.” “I will learn 3 new songs.” “I will join the family at meal times.”

Contracts

Some families create a contract to define and enforce the desired conditions. A caveat for parents is that creating a contract also means creating an authority that must enforce it. Don’t put energy into a contract that will be ignored.

Contracting should be done collaboratively, where the children and teens have full participation in the creation of the conditions and sanctions. The contract needs to be consulted frequently, and revised whenever it proves to be ineffective or unsuccessful.

Parents need to admit that they, too, might be abusing their device time and activities. What’s good for the goose is good for the gander, and they might write themselves into the contract, pledging to ignore their devices during family time.