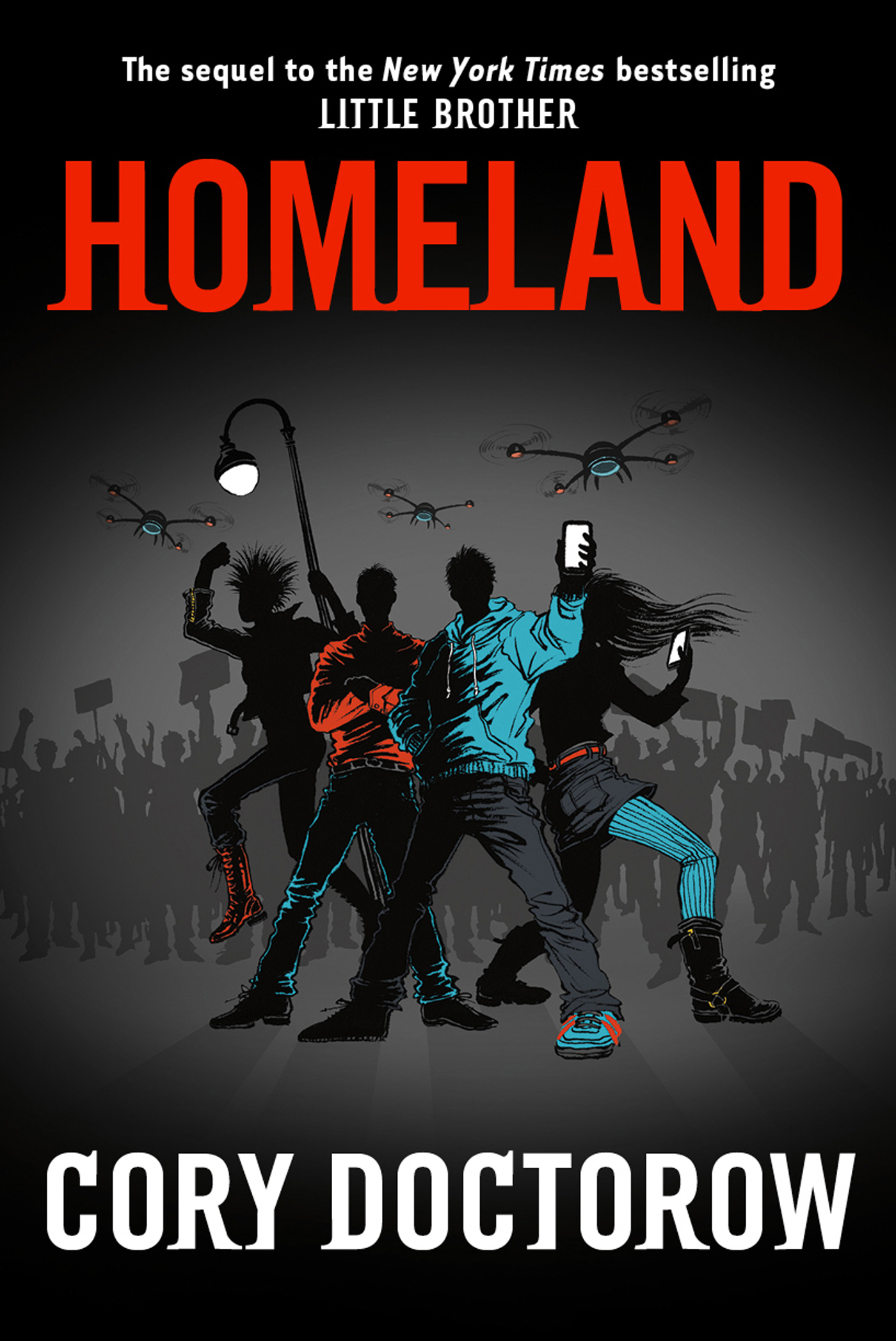

Homeland, by Cory Doctorow — a review

I was once asked what novel I would recommend for a media studies high school course. My immediate reaction was, “Why would you put a novel on the course at all? There are novels studied in every other English course. Use the media course to study literature other than novels, like movies, TV commercials, messaging, websites!” The teacher would not accept that response. I couldn’t talk him out of a novel. He settled on Being There (1970). But Being There is an inauthentic media studies novel. It might focus on television, but it’s 1960s TV. Where is the Twitter back channel? Where is the website with the cast bios, episode previews and fan feedback? Where are the YouTube satires?

This brings me to Homeland, by Cory Doctorow. If you need to study a novel in high school media studies courses, this is it. And if you needed a good novel for English that can inform the course’s media studies curriculum, this is it.

Cory Doctorow is a novelist in the same activist tradition as were Kurt Vonnegut and Mark Twain. Vonnegut’s novels were not just entertaining, but they got under my skin, creating discomfort, a need to re-examine life, a need to do something about the problems he was describing.

Homeland is that kind of novel. But it is also a novel of the 21st century, a novel that speaks to social media, Wikileaks, and covert government organizations that violate people’s rights. It is also good storytelling and good literature. You expect good writing to hold your attention, help you imagine action, sounds, and colors. Homeland accomplishes that well. The characters are well drawn and believable. The pacing is steady and rapid.

And don’t let the Young Adult label prejudice you. The novel does not patronize or condescend. Its action may be youth-oriented, but it addresses issues of illegal surveillance and unlawful detention that pertain to everyone.

Doctorow is billed as a science fiction writer, but his is not the science fiction of aliens from Mars. Rather it is aliens in the form of humans exploiting technology to abuse the rights of others. This is also not science fiction that is unlike our current lives (think Star Wars’ range of aliens, death stars and bizarre planets). If Homeland is indeed set in the future, it is the very near future. And its events are genuinely chilling. In fact, it does not seem like the future at all, but just a very plausible turn of events that might happen next month.

And that plausibility is its gift. It presents us with such credible people and events that readers may wonder if they, too, might soon find themselves similarly victimized. If we can imagine corporations manipulating laws that allow usury interest charges on student loans, if we can imagine ourselves surveilled, kidnapped and tortured by people charged with our protection, maybe we will take preemptive steps to identify and limit government abuses.

Much to his credit, Cory Doctorow does not present the safe, Hollywood-style plot where the hero and villain meet in the obligatory scene, the villain either recanting her evil actions or dying ignominiously. His hero sometimes chickens out, eschews smart-ass banter, and makes mistakes. The villain remains dastardly, and often invisible. The story is, therefore, uncomfortably life-like, where covert operatives not only don’t get caught, but sometimes get promotions or transfers.

In fact, the events of Homeland are similar enough to recent protest experiences, with unlawful arrests and detentions followed by failed prosecutions of law enforcement, that its fictional descriptions read true.

Doctorow included two Afterwords, one by Wikileaks’ Jacob Applebaum and one by Demand Progress’ Aaron Swartz. It is compelling to consider whether these are part of the novel or extensions. I prefer the former interpretation. Each one provides testimony as to the absolute plausibility of Homeland‘s events, affirming the feeling I had that they were as much docu-drama as fictional.

Sadly, Aaron Swartz killed himself while Doctorow was conducting his promotional tour, possibly as a result of the same kinds of governmental persecution as Marcus experienced in the novel. So it is impossible to read Homeland as a work of literature disconnected from its cultural context, but rather as part of the cultural dialogue that occurs between citizens, business and government. That is literature at its best.

To return to Twain, Homeland‘s ending reminded me of Huckleberry Finn. Both novels describe a teen who has survived terrible actions perpetrated by a hugely dysfunctional society. Their responses are very different, and maybe explain the difference between 19th and 21st century America. Huck resolves to ‘lit out for the territories’ because he is sickened by what he has experienced. He is hoping to find—or make—a more amenable world. Marcus’ resolve is to become MORE involved and speak truth to power whenever he can. He knows the risks and believes doing the right thing is worth it. He is fulfilling the mandate set by Cory Doctorow, Jacob Applebaum and Aaron Swartz. He is setting the example for the rest of us.

Homeland is a polemic and a warning, but a necessary and important one. It is a possible projection of the future that is compelling, bears consideration and a good addition to anyone’s reading list.

Cory Doctorow spent several months traveling to promote Homeland. Several of his talks can be found on Youtube, and make for compelling viewing.

He also blogs at www.boingboing.net and maintains a website at www.craphound.com

See also a Homeland study guide and the review of For the Win.