Medieval Times: Finding the intersection of history & pop culture

https://www.medievaltimes.com/toronto

Why would anyone want to relive an era defined by plague, rats, the stench of open sewers and horse poop, risk of torture, and daily threat of violence? It seems many people love the prospect, and will also pay a hefty price to take their children to enjoy it.

Except that this is not the medieval times of yore – especially not the version re-imagined by Monty Python in Monty Python and the Holy Grail (which might arguably be WORSE than the real thing!)

I refer to the corporate enterprise of Medieval Times, the sanitized European medieval entertainment experience. I was privileged to take my 8 year old granddaughter, and very soon realized it offers a goldmine of teachable media literacy moments. There may be educators who might be wanting to plan a field trip to Medieval Times; or have considered using their curriculum in Social Studies or History. They may not have considered that this experience, and their subject, might be considerably enhanced by viewing through a media literacy lens.

As a caveat, the media literacy lens provides a window into reality – ie, it allows us to recognize constructs that contain hidden ideologies, that are economically-driven, and the meanings of which are dependent on the idiosyncracies of the audience. I love these media-literacy glasses permanently affixed to my eyes. However, they can get in the way of spontaneity. In this case, it prevented me from immersing myself uncritically in the environment – at least the way most tourists do. It was fun alright, but not the fun of experiencing the best of medieval culture – but because there was so much to deconstruct! A philosopher said, “It is better to be a human being dissatisfied than a pig satisfied; better to be Socrates dissatisfied than a fool satisfied. And if the fool, or the pig, are a different opinion, it is because they only know their own side of the question.” –John Stuart Mill (1863). I’m not denigrating the average Medieval Times visitor, only noting that it’s just harder to immerse yourself in the environment when it is so obviously someone else’s construct!

Medieval Times is situated in a building space originally belonging to the Canadian National Exhibition, circa 1905, in Toronto. It has retained a certain grandeur in the form of high ceilings and embellishments. Upon entering the great Hall of Arms, however, the visitor is immersed not in Edwardian architecture, but in the visual icons of the warring medieval Spanish states of Catallan, Aragon, and Leon. These include the house brand logos displayed on banners, standards, and pennants. An historical map of medieval Spain (see image) is also prominently and permanently displayed on a wall.

Medieval Times is situated in a building space originally belonging to the Canadian National Exhibition, circa 1905, in Toronto. It has retained a certain grandeur in the form of high ceilings and embellishments. Upon entering the great Hall of Arms, however, the visitor is immersed not in Edwardian architecture, but in the visual icons of the warring medieval Spanish states of Catallan, Aragon, and Leon. These include the house brand logos displayed on banners, standards, and pennants. An historical map of medieval Spain (see image) is also prominently and permanently displayed on a wall.

And since this is a profit-making enterprise, we are surrounded by the glitter of commerce: dragon and unicorn stuffies, gaudy necklaces, and light sabres and wands. (There is a hint of Star Wars, with swords you can light up with a press of a button – so anachronistic). A massive bar dispensing beer and ale dominates the centre. One can opt for a group shot with the beautiful Queen, and promptly post it on Instagram and Facebook. There are many add-ons to round out your experience, and support this savvy, anything-but-medieval money-maker.

And since this is a profit-making enterprise, we are surrounded by the glitter of commerce: dragon and unicorn stuffies, gaudy necklaces, and light sabres and wands. (There is a hint of Star Wars, with swords you can light up with a press of a button – so anachronistic). A massive bar dispensing beer and ale dominates the centre. One can opt for a group shot with the beautiful Queen, and promptly post it on Instagram and Facebook. There are many add-ons to round out your experience, and support this savvy, anything-but-medieval money-maker.

Medieval Times is a construct. Rather, it is a reconstruction, a re-imagining of medieval life without the negative characteristics I outline above. In the comfort of historic hindsight, medieval life suggests a romantic time when men were knights, and women were – well – insignificant (at least until 2018 when a Queen replaced the King after 34 years).

So it is a media construct in the sense that it represents a particular moment in the medieval era through carefully-chosen images and sounds drawn from historical artifacts, literature, and popular culture but more often from media representations and iterations of the time.

The Medieval Times experience presents the visitor with a refreshing respite from our stressful yet sanitized existence. It is a romantic play-fantasy, a diversion, promising a simpler time in which lives could be lost, but we know they won’t really be. We know it’s all pretend, and we play along. It’s fun to pretend; it’s part of the fundamental human need for play, to be part of a story. It’s narrative, it’s theatre.

The romantic image of the knight defending the honour of a female (either queen or paramour), or his country has legitimate origins in literature and history. Knights were part of the elite army of the ruling monarch. Chaucer wrote about the “gentil, parfit Knight” in his 14th-century prologue to the Canterbury Tales (a media construct in itself). The knight represented the paragon of virtue: he loved “chivalry, truth, honour, freedom and all courtesy.” This icon of masculinity has come down to us in many iterations: the animated superhero as well as James Bond, Jason Bourne, and superhero figures. They ‘save the day.’

The romantic image of the knight defending the honour of a female (either queen or paramour), or his country has legitimate origins in literature and history. Knights were part of the elite army of the ruling monarch. Chaucer wrote about the “gentil, parfit Knight” in his 14th-century prologue to the Canterbury Tales (a media construct in itself). The knight represented the paragon of virtue: he loved “chivalry, truth, honour, freedom and all courtesy.” This icon of masculinity has come down to us in many iterations: the animated superhero as well as James Bond, Jason Bourne, and superhero figures. They ‘save the day.’

Medieval Times re-presents the archetype through young, long-haired, fit male actors – outfitted not in chain mail and heavy metal, but in colourful textiles mixed with leather and lightweight lances. As in a videogame, image and sound are reduced to the familiar repetitive iconography of the history books. We are immersed in a communal theatrical experience, therefore, just as videogames are essentially a form of experiential theatre. The narrative is driven by a tense dialogue between the Queen and her advisor, and then extended into the jousting ring by the Knights. The elevated language we associate with Shakespeare and medieval poetry – which was certainly never used in everyday life – is layered on to the visuals.

Medieval narrative tropes offer the perfect escape environment: we can cheer on the dashing hero, boo the (equally as dashing) villain, and egg on our favourite to put an end to the opponent by the most violent means possible. All this while eating food with our hands – a respite from modern manners! Again this is all part of the play, or the play-acting.

Medieval narrative tropes offer the perfect escape environment: we can cheer on the dashing hero, boo the (equally as dashing) villain, and egg on our favourite to put an end to the opponent by the most violent means possible. All this while eating food with our hands – a respite from modern manners! Again this is all part of the play, or the play-acting.

The joust narrative is prefaced with a falconry demonstration, which for this writer was the most dramatic and memorable of the afternoon: the swooping and circling of the bird, desperately seeking freedom, was exciting yet poignant against the backdrop of garish pretense.

The real stars of the show are the superbly trained horses. Like the falcons, they are trapped actors in the whole panorama, and have been taught to perform as unnaturally as possible. The falcon is reduced to not only not hunting, but swooping endlessly in circles; similarly, the horses do not run, but ‘dance’ instead…

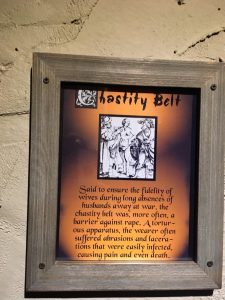

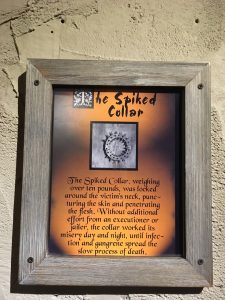

The dark and jarring side to the whole space turns out, ironically, to be the most authentic: the Torture Museum – tucked into a little corner by the restrooms. Original implements are displayed here, including the rack and the chastity belt (ostensibly to protect women from rape … say no more …). The artifacts seem to indicate that medieval times were indeed precarious for the average citizen. These were powerful methods of controlling citizens, and ensuring a predictable environment . The tone is dark here, as it does not celebrate medieval times as much as it presents them soberly and authentically. The juxtaposition with the mainstream entertainment spaces of the Great Hall and Jousting Ring is dramatic.

Are we being encouraged to enjoy the sparkly souvenirs, juicy food, and dramatic stories of chivalry in an attempt to block out, or counter-balance, the nasty (but ‘real’) bits?

So it is essential to remind ourselves (and students) that this venue and performance have very little to do with history. Just as Camelot the musical, or its source, T.H. White’s The Once and Future King, are several iterations removed from reality. (We should recognize, on the other hand, that historical events, by the time they make the history books, suffer from the bias and exaggeration of the writers. And if they don’t make it into the books, it’s often due to suppression by prejudice.)

Educators who might use Medieval Times as a vehicle for teaching about medieval history need to help students distinguish the construct from the reality, and to acknowledge from the get-go that Medieval Times does not present the era, but re-presents it for the citizens of modern times, through the lens of present culture.

Educators can use Medieval Times as a media literacy experience in many ways, across the curriculum. For example, students can research and compare MT to medieval history, from different sources; they can devise their own dramatic versions, giving them a contemporary spin; they can read, write, and produce both analogue and digital versions of medieval literature. All that is needed for the media literacy spin are questions about MT as a media experience. AML suggests using the triangle as a starting point.

Alternately, teachers can use the key concepts.

Sample questions might be:

(Media construct reality)

How are gender, race, age, and class represented in the MT narratives?

What is the role of nature in the MT experience (falcons, horses)?

How are they used to serve MT’s branding purpose?

(Media construct versions of reality)

What aspects of the rituals and details of medieval life are emphasized, and what are omitted, and why?

(Audiences negotiate meaning)

Why might this particular historical era be attractive to today’s audiences?

What gaps in modern life might the performances be filling?

How might different audiences—adults, children, new Canadians—respond to this experience, and why?

(Media contain ideologies)

Compare the ethics and ideals values in the show’s narrative to those of today’s world.

Which values do we no longer hold important today and why?

Why might the values in the MT narrative be nevertheless appealing to 21st century audiences?

(Media have economic implications)

Make a list of the commercial products sold at MT. How do they relate to medieval history and to 21st century life: how are they modified, and why? How do they relate to 21st century life?

How do they accentuate, or make memorable, the experience of MT?

-by Carol Arcus

(This blog and its lesson ideas can be applied to Elementary and Secondary classrooms – ed.)