Podcasts—the new old medium

Apple iTunes

Podcasts have become an interesting new/old media phenomenon. While they seem to be the new de rigeur form, they arguably date from electronic media’s second-oldest form: radio. (The first is the telegraph.) Radio talk shows—in the form of interviews, dialogues or monologues—have been industry staples forever.

Why podcasts are suddenly exciting is therefore a bit of a mystery; and likely a source of humour for people who have made a career of radio hosting. Perhaps it is more useful to explore the form differences between radio and podcasts than the content, which is arguably little evolved.

Fox

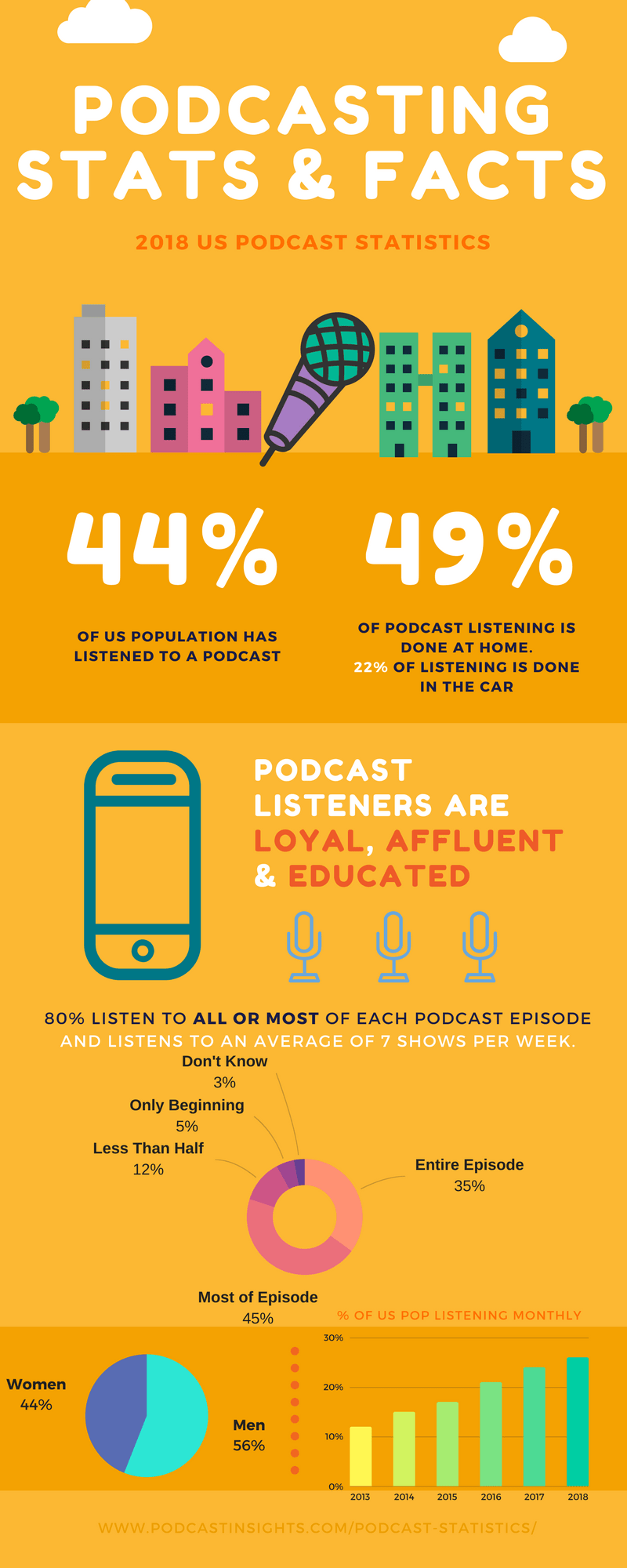

The radio shows that predated podcasts were ad-supported and broadcast to anyone with a receiver—eventually everyone. Measurement companies, e.g., Nielsen and BBM, tracked audiences via self-reporting phone calls and mail-in diaries. Advertisers used the data to select the best program placement for their ads; broadcasters used them to determine cancellations, new shows and ad rates. Vestiges of this system can be seen most transparently during the Superbowl, where companies spend millions on ad time to reach specific audiences.

https://www.rossmediasolutions.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/2019-podcast-stats-infographic.png

The Canadian Radio and Television Commission provides broadcast licenses based on content, licensing a maximum number of sports, country, or hard-rock stations in any given market to ensure audiences are served and broadcasters have unique cultural territories. The wild-west nature of podcasting allows as many different and similar podcast forms and contents as creators are willing to provide.

https://www.spreaker.com/episode/the-rise-of-zero-proof-cocktails-and-alcohol-free-spirits-in-canada–22403134

Podcasters’ revenue streams are of two major types: ad-supported and listener-supported. Some combine these, or offer both forms, where paying subscribers receive ad-free versions. In both forms, podcasters seek enough steady cash-flow to ensure financial stability, but it’s a dog-eat-dog environment.

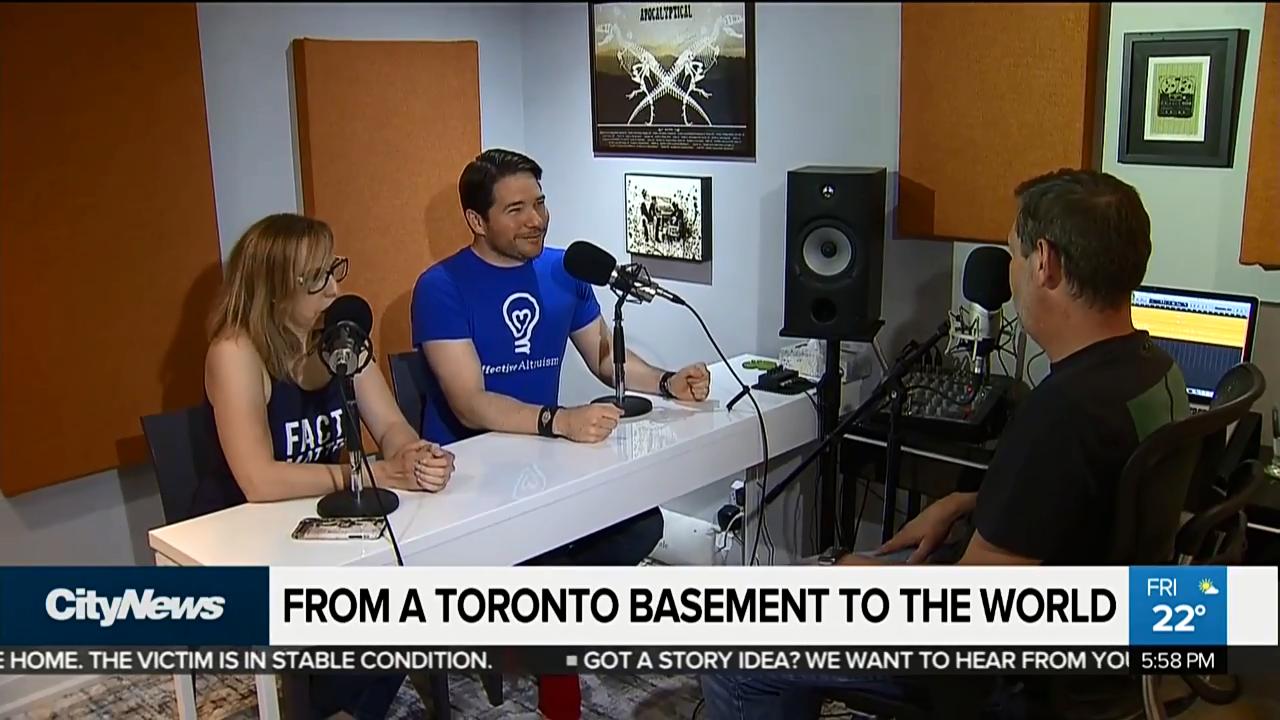

We also need to consider the form, style and address of podcasts when exploring their emerging popularity. Radio—at least in its interview, dialogue and monologue forms—is arguably a very intimate experience. We feel as though the speaker is speaking only to us because she/he is very close to the mic, speaking in high-quality, measured, quiet tones, as though beside us.

The combination of high-quality sound and in-ear presence has made podcast listening a hyper-intimate and personal experience. Given the proliferation of availability—over 500,000 podcasters producing millions of podcasts—users can access content both personally relevant and pleasing. We can listen to what we want, when we want it and wherever we want, all in digital quality. What’s not to like?

CityNews (Rogers Digital Media)

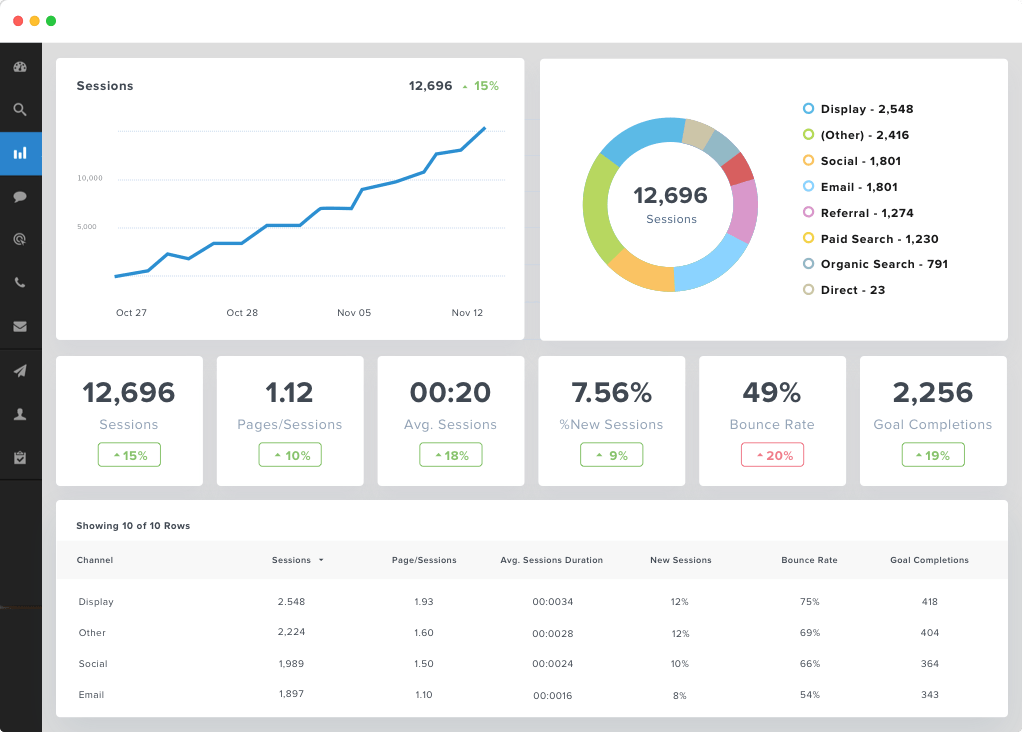

A significant difference between radio and podcast audiences lies in how much creators know about them. Radio creators rely on the Nielsen and BBM data to measure and know their audiences: e.g., address, age, sex, income and education. If podcasters track their listeners and purchase digital data from third parties—search engines, games, social media—they can get even more cross-referenced detail: gender, income, purchasing habits, values, marital status, religion, buying habits, travel habits, location, aspirations—the whole psychographic package. This significant information differential is possible because knowing someone’s physical address provides less useful information than knowing their digital address and their minute-to-minute digital activities.

https://ux.stackexchange.com/questions/123759/what-metrics-to-track-usability-of-a-analytics-dashboard

So podcasting allows listeners to know more and select more personally-pleasing form and content. It allows podcast distributors to sort and promote podcasts to highly-profiled listeners. It allows podcasters to know more and design their form and content for specific audiences to maximize their effectiveness, their profit, or both.