Smartphone Ban Reflections by Neil Andersen

Ontario is one of several jurisdictions currently enacting smartphone bans in public schools. It might seem strange to see this legislation arise some 15 years after the smartphone became popular. Their take-up by teens has occurred slowly since parents bequeathed their old phones. And let there be no mistake: teens-with-smartphones was largely the idea of parents who wanted instant access to their children. Now the ‘chickens have come home to roost:’ most children have smartphones, use them, and adults are rethinking their actions and—in some cases—trying to redress them.

This seeming late-to-the-game ban might be an example of a concept described by media scholar Marshall McLuhan, who stated that we most often notice effects before we notice causes. Some of these effects include mental health challenges, especially among teen women, abbreviated attention spans, and an apparent addiction to social media.

causes and effects

The jurisdictions moving to ban smartphones in schools are attempting to control what they see as the cause, namely the smartphone. This is partly true, but there is more to the issue. The smartphone is a piece of hardware: tangible, visual and audible. But it is more a symbol or metaphor for the effects we have noticed. The smartphone creates an environment via its combination of hardware and software that, in many cases, overwhelms us. It is ubiquitous, available, powerful and personal.

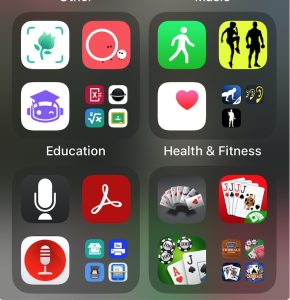

In early smartphone days, the devices were mostly portals to the internet, specifically email and search. Now, however, the apps are portals to a cornucopia of information and services. The early days of Twitter were characterized as providing a ‘fire hose of data.’ This is still true, but now Twitter-come-X is one of a suite of apps that perform a wide variety of services beyond social media. Our smartphones are cameras (with easily-shared images and videos), GPS, weather forecasters, social venues, traffic navigators, calendars, diaries, remote controls, scanners, etc. Each of these innovations occurred over time but have now aggregated into an immensely rich and powerful system. And young or old, we love them. Smartphones and their apps have made users cyborgs. We live with and through them.

‘smart’ has two meanings

We have also discovered that the smartphone has two sides—that ‘smart’ has two meanings—depending on whether we are the user or the service: smart can provide users with a range of useful services but smart can also track and report locations and activities to corporations, law enforcement and governments unseen and unknown. Fortunes are being made regularly harvesting and selling user data without our permission or awareness.

These are good reasons for jurisdictions to be concerned, but maybe a smartphone ban is neither appropriate nor enough. It could be that these jurisdictions have imagined a simple solution to a complex problem—that they can appear to be taking action without delivering desired benefits. So we have to ask ourselves if a ban is appropriate and a real solution rather than a continuing dilemma.

Education is often about empowerment. One goal of education is to help students become autonomous, which means that they understand and can use critical thinking strategies to make decisions in their own best interests. Certainly we wish this for them when they are adults. Considering the huge selection of smartphone apps and services, critical thinking strategies are crucial and are becoming more crucial day-by-day. Arguably, the rapid evolution of artificial intelligence is accelerating and exacerbating this imperative.

The environment created by smartphones—in concert with the internet they connect to—is intoxicating. Consider your own first discovery of what you could accomplish using the power and range of smartphone apps. Small wonder that children first experiencing a smartphone interaction appear mesmerized. It’s like their own genie in a lamp. While their trances may diminish over time, the enchantment remains. So it is for all of us and continues to be as new and exciting apps are launched.

The intention of bans is to limit students’ access to and uses of smartphones. Imagine their distress when services they take for granted and use at will outside of school are limited or removed. How might this influence their educational experience and attitude towards schooling? Might it be taking an already seriously antiquated system and making it more irrelevant?

At home and in classrooms up until now, smartphone use has been discretionary and spontaneous. Specifically, students activate and use their smartphone apps as needed to accomplish a range of tasks. That discretionary and spontaneous experience will disappear with a ban. Giving teachers discretionary powers to allow smartphone use when desired will not fix this. The teachable moment will have passed before teachers find a smartphone in the bin, give it to the student and wait for a response.

student-teacher relationships – teachers as police

Another casualty of the ban will be student-teacher relationships. The way that most bans are phrased dictates that teachers will confiscate smartphones, either en masse at the beginning of a class or as they might notice inappropriate uses. This framing turns teachers into police. Pedagogy works better when students and teachers are co-learners. The co-learner relationship is especially appropriate in digital media literacy studies because students often know the apps and technologies better than their teachers. The teachers can be critical thinking experts while the students can be app experts. What might happen to the hard-won rapport between student and teacher when a teacher confiscates one of the most important communications tools in a student’s life?

teachers as custodians

Placing smartphones in a bin on the teacher’s desk sets the teacher up as a custodian. What might happen if one of these thousand-dollar pocket computers goes missing? Is it tough luck for the student? Is the teacher responsible for replacing the smartphone? Will the school board or government indemnify the devices against loss, breakage or theft? Can students and teachers concentrate on learning, or will they be distracted by the sequestered smartphones? These questions are inevitable and must be part of the banning discussion. This scenario has already occurred by the way, and it was neither pretty nor nurturing. The teacher was deemed responsible for the replacement of the smartphone. Imagine the effect on that student-teacher relationship, not to mention the teacher-principal relationship.

Whether bans are an appropriate response to smartphones in classrooms or not remains to be seen. If they DO reduce students’ anxieties and distractions, great. The opposite is also possible. But issues of responsibilities, relationships and learning will have to be considered and given space.

The fact that several jurisdictions will be exploring and enacting bans simultaneously provides us with a natural opportunity for inquiry (The AML is a big fan of inquiry). Noting the different ways that the policies are constructed and applied, and their resulting effects, will provide media literacy students with compelling and relevant learning. Stay tuned.