Why must there be villains?

by Neil Andersen, Carol Arcus, Margie Keats, Diana Maliszewski and Michelle Solomon

How could victims need rescuing without villains to abuse them?

How could a hero demonstrate heroism without a villain to confront?

How could a plot reach its climax without a villain to defeat?

Heroes may be stories’ main characters, but are villains the plots’ unsung heroes?

These lessons invite students to use inquiry, reflection and discussion to explore the nature of villains and villainy and the functions of villains in stories and in real life. There are many options, so teachers and students are invited to choose which of the many inquiries they wish to pursue.

Warm-up activity

How many villains can you name?

What makes the villains villainous?

How might we recognize villains in stories?

How do you feel when you find a villain in a story?

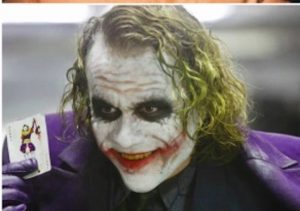

Inquiry 1 Villainous Looks

Do an online image search for ‘villain.’

How do the looks of the characters tell audiences that they are villains?

Look for patterns in the ways that villains are represented.

E.g., What do you notice about their faces? …about their bodies? …about their colours?

Is there a villain that does not fit the pattern?

How might you explain why the pattern is not consistent?

Are there more female villains or male villains?

Explore the images you searched. Choose one.

Answer the questions above based on your selected image. Present it to the class.

Explain what makes your selected character a villain and how well she/he fits with the patterns.

Inquiry 2: Types of Villains/Villainy

Are there different kinds of villains and villainy?

Is there a range, e.g., annoying to horrible?

Look at the following list of villainous qualities or create your own list, then place the items left-to-right in a range from the least to most villainous.

annoying nasty murderer criminal larcenist arsonist thief rapist pedophile bully liar

What might this range of villainy help us realize about villains?

When you hear the word, “villain,” do you imagine a male or a female character?

Are villains mostly male, or are there an equal number of female villains?

Some people think that ‘villain’ automatically means a male, and an evil female must be called a ‘female villain’ or a ‘villainess.’

Why do you think that might be?

Why might it matter whether a villain is male or female?

The word ‘villain’ has a long history, beginning with the Romans.

How do villain‘s old meanings carry into the current ways villains are represented?

Are most villains low-class characters?

What conclusions can you make from your inquiries

Pete is Disney’s first villain. He menaced Mickey and Donald in the early cartoons, but he has been modified over the years. His current representation can be found here and his early look can be found here. How has Pete changed? How might the changes in representation have affected his villainy to audiences?

Inquiry 3 Children and Villains

After discussing the questions below, select the ones you are most curious about and survey people (classmates, family, friends) to find out what most people think. Share your results.

Why might some people think that children should be protected from learning about villains?

Why might other people think that it is important for children to learn about villains?

Where might children learn about villains?

Should children learn about villains mostly from their parents, from songs, videos/movies or from books? Why?

Should children learn about villains alone or with other people? Why?

If you think that children should learn while with other people, what other people would be best? Why?

Inquiry 4 Real-Life Villains

Name or research some real-life villains.

How do real-life villains differ from fictional villains?

How are they villainous, i.e., in what ways are they bad?

Do real villains look as villainous as fictional villains?

Charles Manson organized a mass murder and spent the rest of his life in prison. (AP Photo)

Paul Bernardo raped, kidnapped and murdered several women and is spending the rest of his life in prison.

How might we use our knowledge of story villains in our real lives?

Might story villains who look evil prevent us from recognizing real-life villains?

What do you think is the best way to learn how to respond to real-life villains?

Inquiry 5 Eurocentric cf. Indigenous Villains

North America’s major narrative/story tradition (a story structure brought by European immigrants) is largely Eurocentric—more specifically Greek. Key characteristics of Eurocentric stories are heroes and villains, conflicts, rising action, climax and falling action.

It is useful to explore some Indigenous stories to see their alternative narrative structures and villains. Many have no villains but use characters—often animals—as a story element to move the plot and deliver a message.

Many indigenous stories are explanations of how animals or phenomena began while others describe how people might relate to one another or to nature. Almost all indigenous stories present a worldview in which people and their environments live cooperatively rather than in conflict with nature. Students might explore Eurocentric and indigenous stories using an inquiry question like:

How do Eurocentric and indigenous stories differ in their uses of villains and conflicts? or

How do the the uses of villains and conflicts reveal differences in the worldviews of Eurocentric and indigenous cultures?

Qalupalik (kah LOO puh lick), a fearsome Indigenous sea creature on the lookout for disobedient children, incarnates the dangers of the sea for Nunavut children. Watch the video version of this story here and discuss how Qalupalik is represented.

Does Qalupalik look and behave like most North American villains?

You might also watch and explore the representation and uses of villainy in Lumaajuuq, another Nunavut story.

Inquiry 6 Appearances vs. Reality

Disney’s version of Beauty and the Beast is a useful study in villainy. A major part of the story involves the Beast’s redemption from selfish to self-sacrificing. Gaston—seen here—is represented as a handsome, popular (self-sacrificing) hero early in the story, yet reveals himself to be the real (selfish) villain. The evil-looking Beast—seen here—is the real hero.

How is Gaston’s villainy essential to the Beast’s redemption?What might audiences learn about heroic appearances and villainous behaviours from this story?

Inquiry 7 Manufactured Villains

There are real people who are represented as villains, often in news reports or documentaries. Whether they are villains or not depends on who is looking, i.e., the audience. Audiences negotiate meaning is a media literacy key concept that means that audiences determine what is true, sexy, evil, heroic, etc. Donald Trump represented Kim Jong-un, the leader of North Korea, as a villain, calling him “Rocket Man”. North Korean leaders have represented the USA—and especially Donald Trump—as a villain, calling him a “Dotard.”

How has each group used the codes and conventions of villainy to represent one another?

How did these representations of the enemy as a villain help each man maintain his power and popularity with his people?

What other examples of manufactured villains can you find?

Inquiry 8 Villainy as a traumatic response

Some villains have backstories that reveal abusive experiences that led to their villainy.

Can you think of any examples of such villains? (e.g., V in V for Vendetta)

Consider Spiderman and Batman, who are seen as heroes by some characters but as villains by others.

How is Bruce Wayne (Batman’s secret identity) different in the way that he reacted to the childhood trauma of seeing his parents murdered?

Why might his reaction be important to the people in Gotham City?

Why might his reaction be important to consumers of Batman stories?

Inquiry 9 Can characters be both heroes AND villains?

Who are the villains in Riverdale?

Are they consistently villains, or do some of them switch between heroic and villainous? (This change is called a ‘heel-face turn’ by script writers.)

If you know Riverdale well, graph the villainy of some characters over the course of several episodes. Jughead and Cheryl might be useful characters.

Black Panther presents a very complex and interesting villain. Killmonger, like Bruce Wayne, responds to childhood trauma. He becomes a mercenary and a killer, but is he a villain? Are his ideas about helping oppressed people wrong? Was he right to reject Black Panther’s offer of redemption? How might the story have changed if he had accepted redemption?

Using your knowledge of Riverdale, Black Panther or another story that you might know better, reflect on and provide a response to the inquiry 6 question: Can characters be both heroes AND villains?

Inquiry 10 Canadian Villains

Are Canadians anyone’s villains?

Do a search for ‘Canadian villain.’ What do you find?

Did you find a Canada Goose?

Why might a Canada Goose be considered a Canadian villain?

What might finding a goose in a search for Canadian villains say about Canada and its villains?

What other Canadian villains did your search locate?

What villainous qualities do these villains have?

Why might it be important for Canadian students to know that there are Canadian villains?

You might have heard of Dr. Norman Bethune, a Canadian doctor who served with Chinese Communist forces until his untimely death in 1939. Dr. Bethune has been both a villain AND a hero, making the change sometime around 1970, many years after dying.

Why might Dr. Bethune have been considered a villain in Canada for 30 years?

What changed in the 1970s to re-define him as a hero?

A statue of Louis Riel stands behind the Manitoba Legislature, yet Riel was hanged as a traitor to Canada.

Why was Louis Riel considered a villain in Canada?

What changed to re-define him as a hero?

Inquiry 11 Manufacturing Canadian Villains

Canadians have also used villainous representations in their media.

How have the codes and conventions of villainy been applied to Prime Minister Justin Trudeau?

Why might the Conservative Party want to represent the Prime Minister as a villain?

Has the Liberal Party tried to represent any of its opponents as villains? How?

Who else can you find who has been represented as villainous?

Who gains from these representations? How?

Hint: research Canada’s Prime Ministers, immigrants, indigenous people.

Inquiry Conclusions

Consider your inquiries into villains and villainy.

What advice would you give someone curious about villains and villainy?

*(Feature Photo Credit – IMDb )

(These ideas are adaptable to both secondary and elementary classrooms. – ed.)