Password revelations as a privacy site of struggle

One of the most compelling aspects of media studies involves sites of struggle. Sites of struggle are social phenomena that become arenas for changing values and behaviours. They include fashion, legislation, food and art. Canada’s gay marriage law debate was a site of struggle over shifting attitudes and legal support for same-sex unions. Similar laws have been passed—or seem unlikely to be passed—in other countries, signaling those countries’ struggles with these issues.

Teen activities are an evergreen site of struggle. “What’s the matter with kids today?” is a question asked perennially, beginning with Aristotle. Teen values and behaviours are a constant source of news headlines, head shaking and parental anxiety, often because adults equate youth with angst about change.

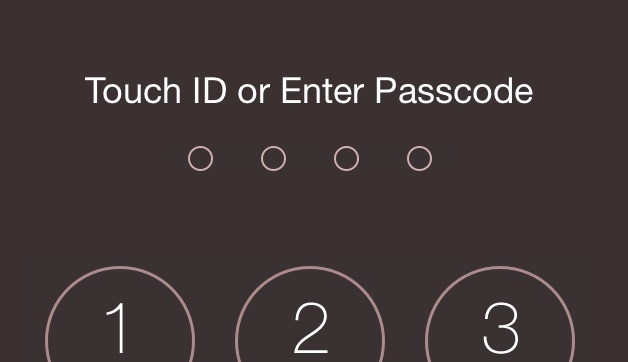

Password privacy has emerged as a provocative site of struggle. See here and here. Law enforcement officers have always searched suspicious premises and persons for suspected illegal objects. Now, it appears, Canadian border guards can legally insist that people entering Canada —including Canadians—divulge their smart phone passwords so that agents can search them for illegal content. Online files can be and are transmitted across borders at any time, so it seems strange that government would view seizing files at a border crossing as an effective way of keeping them out of Canada.

Toronto Sun

Legal experts are uncertain how to respond to these developments. Seeking analogous situations fails to provide clearer understanding of the issues. It is new territory in many ways, and therefore a wonderful media literacy discussion opportunity.

Some powerful discussion questions might include:

Canadians seem to enjoy more privacy rights inside Canada than they do when entering Canada. Why might the Charter of Rights and Freedoms not fully apply to Canadian citizens during their re-entry?

Luggage and body searches are commonly executed to find illegal items: firearms, explosives, drugs, banned live animals, animal parts or foods, etc. But these are physical items. Some charges have been laid involving the importation of child porn files found on computer hard drives.

What else might be arguably imported on a smart phone? Images? Music? Videos? Texts? Speeches? Emails?

And what criteria might agents apply to determine which of the thousands of files qualify as illegal?

Smartphones have files stored in their memories but also links to online files. The files are not physically on the devices, but the links are.

Might Canadians be charged for possession of files AND links to files?

Might links be considered illegal if they connect to ideas and information deemed illegal?

Should searches be restricted to items located on the devices, while items that the devices link to be ignored?

More specifically, should law enforcement agents be limited to searching a device in ‘airplane mode’ or be allowed to search it while it is wirelessly connected?

iPhone memories range from 8 to 128 gigabytes. Logistically, how much time and effort might be required to search and assess the data on smart phones?

Who will perform the search?

Should the searchers be government employees or outsourced employees?

Should the searches be conducted in Canada or might the data be transmitted electronically to foreign contractors for examination?

Who will fund the searching costs?

What criteria will they apply?

How well might their judgments hold up in court?

For how long might agents reasonably confiscate someone’s device?

Should agents be allowed to make copies of files?

For how long might agents search a device before deciding to lay or drop charges?

With what other law enforcement agencies—foreign and domestic—might border agents share what they find?

For how long might data be retained in government databases after a case is settled or a smart phone is returned?

If data is shared with foreign governments, should those agencies be compelled to delete data? After how long?

Edward Snowden’s actions are a clear demonstration that a private citizen (read non-government employee) with a particular ideological point of view can leak information gathered and shared by international government agencies.

If Canadians comply with agents’ requests for passwords, what expectations should they have that their data is kept private?

What guarantees should there be to keep information private?

What penalties should the government suffer if it leaks personal data obtained during a border search?

Bill C-51 uses the term ‘terrorist,’ stating that its purpose is to search for and identify people who might be planning terrorist activities.

How does the bill define ‘terrorist’ and ‘terrorist activities?’

Might activities that oppose government positions (e.g., protests, emails, speeches, sit-ins, occupations, podcasts, rants, songs, cartoons, T-shirts, etc.) be considered terrorist acts?

What are the limits of Bill C-51?

Forced password revelations at border crossings and Bill C-51 have provided great opportunities for Canadians to explore privacy and surveillance in the wireless environment. I hope that some of these questions provoke examination, reflection and help Canadians understand and appreciate the need for—and benefits of—media literacy.

(These lesson ideas are adaptable to a secondary school classroom – ed.)