Young Children’s Book Awareness as Media Literacy

Many parents make a particular point of exposing their children to books at an early age and continue to promote a love of reading throughout their childhoods. As popular as tablets and smartphones may be, many parents still privilege books and reading experiences over other media experiences. (We rarely hear, “No books until you finish your broccoli!”) Many teachers also make a production of ‘story time,’ where children gather on the carpet and teachers do a read-aloud of a picture book accompanied by short discussions of the characters and the story.

One effect of this parental/teacher approval and aggressive book use might be that children come to see books as the preferred or normal ways of consuming stories, while the animations, games and songs offered on tablets and phones are—by comparison—seen as less important, possibly even frivolous.

Another result of these practices could be that books are seen as benign or neutral media forms when compared to other media experiences. Books, however, are built from words and images and are as much media constructions as any other media form. As such, they should be subject to the same scrutiny and understanding. This is especially true for picture books that communicate to children on many language levels (words, fonts, colours, shapes, images, symbols, metaphors, etc).

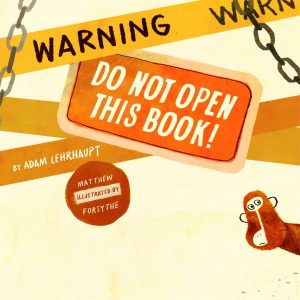

It might be challenging, however, for parents and teachers of young children to find resources that support critical thinking about books. i.e., the codes and conventions of images and words and the readers’ role in the reading process. Which brings me to Adam Lehrhaupt and Matthew Forsythe’s WARNING: DO NOT OPEN THIS BOOK! and PLEASE, OPEN THIS BOOK! (Simon and Schuster)

These two books, especially when experienced together in a compare-and-contrast exercise, support critical thinking about book forms and audience address. They can enhance children’s understanding of reading and the functions that books and readers play in that transaction. I use the word ‘transaction’ because reading is a give-and-take process: authors and illustrators provide information; readers provide the mental work to understand the words and images and how they work together to provide meaning and pleasure.

This is also media literacy.

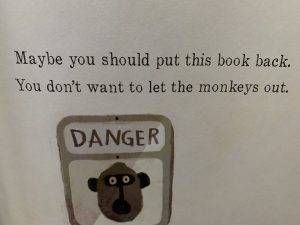

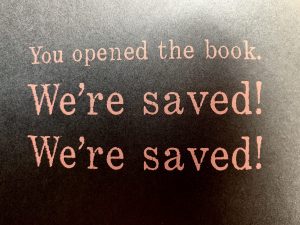

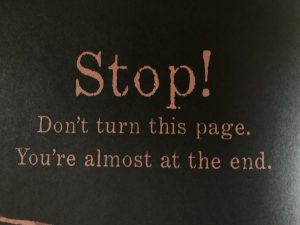

In WARNING: DO NOT OPEN THIS BOOK! Lehrhaupt presents not so much a story as a crisis point within a longer story; a crisis that implicates the reader as crucial participant. The book addresses the reader directly in imperative voice (“DO NOT OPEN THIS BOOK!”), meaning that each page either commands or pleads with the reader NOT to read the book and thereby avoid dire consequences.

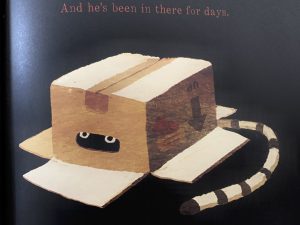

Opening the book and continuing to turn the pages releases monkeys, macaws and an alligator by degrees, all of which contribute to chaos. The narrator explains that only closing the book and trapping the animals inside will save the story. It’s great fun, and involves readers in understanding a reader’s role in the book-reading experience, i.e., readers have to participate by turning the pages in order to complete the reading experience.

Parents and teachers doing a read-aloud with children can have a great time learning about story and graphic codes and conventions.

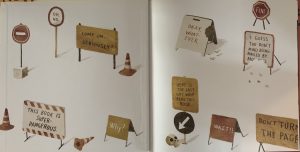

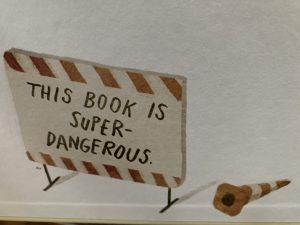

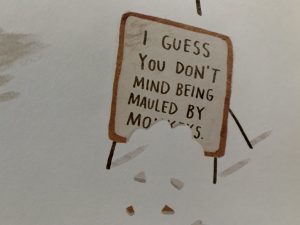

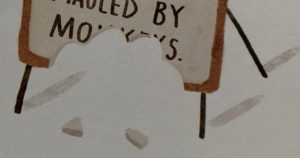

For example, the inside page of the cover is a significant prologue to the story, not just decorous illustrations. It sets the tone using signage.

Children can be prompted to recall and describe where in their non-reading lives they have seen signs used and how they often warn people of hazards.

Then they can connect the signs on the inside cover to the story events and the tension that they create in the reader.

Inferencing can even be introduced into the reading conversation by exploring the sign that has been ominously damaged by unseen forces.

Close examination of one damaged word reveals the threat. Children can discuss how the sign might have been damaged and how the damage itself adds to the danger and intrigue of the story. The partial word forces readers to participate—to use a Cloze procedure (trial-and-error guessing like we do when completing crossword puzzles) to discover that the damaged word is MONKEYS—making the story more interactive and enjoyable.

Reader address is a special and useful feature of WARNING: DO NOT OPEN THIS BOOK! Rather than observing a monkey’s adventures with other animals as a voyeur external to the story (e.g., Hug), the readers of WARNING: DO NOT OPEN THIS BOOK! are instrumental participants in the progress of the story.

The narrator implores readers NOT to open the book or turn the pages. Their curiosity, however, and innate thrill of defying authority will cause them to continue turning pages.

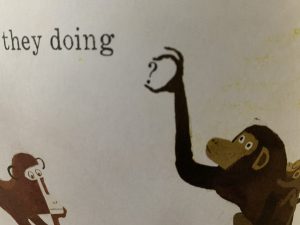

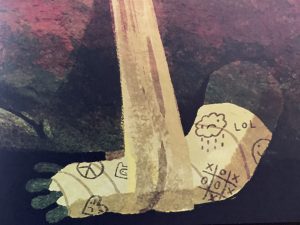

Illustrator Matthew Forsythe also had fun with the interactions between the words and the images. To illustrate and reinforce the anarchic spirit of monkeys and their threat to the order of the story, he represents them as interfering with the punctuation and word structures. Children can be prompted to figure out where the ? belonged before the monkey grasped it and how removing it from the sentence disturbs the meaning of the story.

All of this adds to the chaos that the narrator is urging readers to avoid. It isn’t just the chaos of monkeys and macaws charging around inside the story, however, it is also the vandalizing of the sentences that are telling the story. These monkeys are threats to the story itself—they MUST BE STOPPED and the narrator is depending on the readers to stop them.

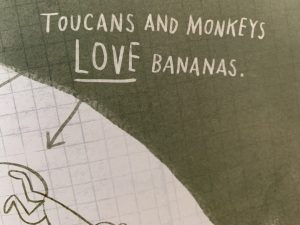

The graphic design of one page is completely unique and children might be prompted to wonder why that might be. Its background is green and grid paper provides the background for line drawings of the animals. Why is it so different? A key word to help children make sense of the graphic codes and conventions is ‘PLAN,’ which labels the page as not what is happening, but what the reader and narrator hope will happen—an imagined ending that can occur only if the reader takes the narrator’s advice.

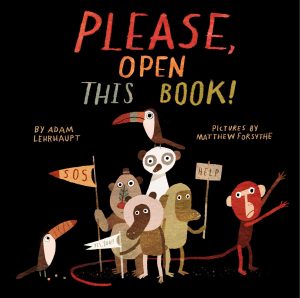

Book awareness can become even more profound when WARNING: DO NOT OPEN THIS BOOK! is compared to PLEASE, OPEN THIS BOOK!

WARNING: DO NOT OPEN THIS BOOK! was written first and involves trapping the animals inside the book to keep the story safe from chaos. PLEASE, OPEN THIS BOOK! involves opening the book to release the animals who have not only been trapped but injured when the book was slammed shut at the end of WARNING: DO NOT OPEN THIS BOOK!

In WARNING: DO NOT OPEN THIS BOOK! the reader is represented as a hero for trapping the animals and preventing chaos. In PLEASE, OPEN THIS BOOK! the reader is represented as a hero for releasing the trapped animals.

In both cases the reader plays a crucial role. The importance and agency of the child reader is very attractive and parents/teachers can discuss how the active reader position is making the story more enjoyable.

WARNING: DO NOT OPEN THIS BOOK! is presented in black text on white pages while PLEASE, OPEN THIS BOOK! is presented as red text on black pages. Children can look at sample pages from each book and be prompted to consider how the white pages and black pages of the stories influence the feelings they have towards the stories. The black pages are not just a whimsical design decision but might help readers understand and appreciate the darkness that the trapped animals have been living with while imprisoned in the book.

Rather than a one-time read-through, which might be appropriate for many books, WARNING: DO NOT OPEN THIS BOOK! and PLEASE, OPEN THIS BOOK! can be revisited and pondered as both stories and book forms.

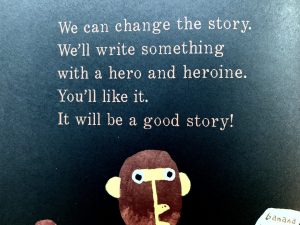

For example, one page offers to change the story if only the reader will agree to leave the book open and keep the animals free from harm.

This is a great opportunity to imagine what kinds of hero and heroine might be added, and if that would improve the story or change it so much that it would lose its momentum of saving the animals and ruin its pleasure. Children can become book critics.

Parents and teachers can even introduce the idea of sequel by exploring how WARNING: DO NOT OPEN THIS BOOK! provides background information to the events in PLEASE, OPEN THIS BOOK! and how PLEASE, OPEN THIS BOOK! re-uses the animals and props from WARNING: DO NOT OPEN THIS BOOK!

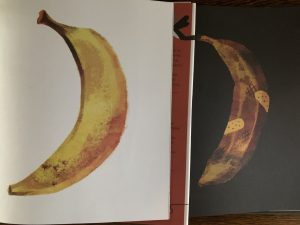

For example, the banana in WARNING: DO NOT OPEN THIS BOOK! reappears in PLEASE, OPEN THIS BOOK! but has suffered damage as a result of the readers’ actions.

Parents, teachers and children can have great fun learning how books and stories work: how words and images work together to communicate and bring pleasure and how readers must work and participate in the reading process to make sense and complete the stories. These are important and useful media literacy concepts that might then be extended when discussing other media experiences.

Extension

Strategies introduced in the reading of these books might be applied to children’s general reading experiences.

Specifically, readings might be paused while readers examine ways in which the illustrations are adding to the story progress and enjoyment. Readers might ask,

“What do the drawings encourage us to notice?”

“How might the drawings encourage us to think?”

“How else might this page be drawn?”

“What might happen next?”

“What ELSE might have happened next?”

“What do you think the author or illustrator might want us to think about on this page?”

“How is this page encouraging me to think about the character or the events?”

What a wonderful lesson. I am ordering those books today!

Hey Jeff, that’s great. It’s Carol Arcus here, I just got Neil’s tweet and read it too. He was so enthusiastic about these books, and, like me, realized how really smart they are. I’ll pass this on. We look forward to chatting with you on our podcast soon!